Oliver Stone’s “U-Turn” (1997) is rarely mentioned in conversations regarding Stone’s best work (or at all) and that needs to change.

Made between “Nixon” (1995) and “Any Given Sunday” (1999) and released to audience indifference in 1997, it’s not the minor league lark that many claimed in ‘97. Actually, this is Stone’s “After Hours” (1985) in which an ensemble cast, a can-do film school approach and a light footedness elevates it above prestige expectations.

Yes, its “smaller” than “JFK” (1991), Stone’s masterpiece, and less important than “Platoon” (1986), Stone’s defining work. Yet, “U-Turn” is never afraid to leave teethmarks on its audience (as opposed to holding their hand and coaxing them towards a Happy Ending) and is wall-to-wall with Stone’s brilliance as a film artist.

We meet Bobby, played by Sean Penn, on the run, driving through brutal roads that have used up all sorts of wildlife and are unforgiving to those lacking survival skills. Bobby himself must face this when his car pops a gasket and he’s forced to surrender his vehicle to a folksy, dirty (in every sense of the word) and weary mechanic named Daryl (Billy Bob Thornton).

While awaiting repairs, Bobby walks into a run-down little town called Superior and seemingly gets into trouble with everyone he encounters. A bigger problem lies in Bobby’s past, as we learn he’s on the run from criminals, has a massive stash of money in his possession and even lost a finger for missing a payment to the wrong people.

When Bobby encounters the enticing Grace (Jennifer Lopez) and her bizarre husband Jake (Nick Nolte), he falls into another self-made trap, involving murder-for-hire and a femme fatale who might be the deadliest of all the dangerous creatures he encounters.

We’re deep in a film noir world, as Nolte notes “a man who’s got no ethics is a free man.” The $50,000.00 life insurance policy that becomes a murder/swap scenario plot point is like something right out of “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (either version).

John Ridley’s screenplay is based on his “Stray Dogs” and clearly reflects a love for these seedy and deliciously nasty types of crime stories.

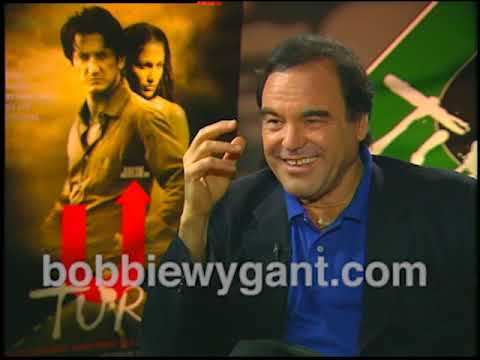

25th Anniversary: U TURN (1997) Oliver Stone pic.twitter.com/MiNHgolSQd

— Cinema Phenomenology (@phenocine) August 27, 2022

When Penn and Lopez’s character dream of escape, it’s not an island oasis they envision, but a shot of a car roaring down a road, smoky dirt flowing behind it. For these fallen angels, money, sex and one-upmanship is a goal but true salvation is fleeing the purgatory in which they cook under the roasting sun.

Stone’s mastery of tone and use of full throttle cinema to evoke the protagonist’s perspective is as strong as ever. So is the excellent ensemble, as every cast member plays to their strengths and surprises us with some offbeat acting choices.

Early into production, the lead role was once played by Bill Paxton but wound up in Penn’s hands; Penn’s testiness makes him a better pick for the role than the more amiable Paxton.

It helps that we’re not really supposed to like Penn’s character, though he acts as the audience surrogate and we want him to get out of Superior as much as he does.

A pitch perfect Claire Danes and Joaquin Phoenix intermittently show up as a deranged young couple. Thornton is fantastic playing Daryl, the local mechanic whose lone ability under a hood gives him god-like abilities in this town.

It also creates a sense of division between Bobby’s dismissive, above-it-all tourist and Daryl’s folksy knowledge and practical approach to everything. Penn’s scenes with Thornton are hilarious, as we share and understand Bobby’s rage, but Daryl is always right.

Jon Voight’s casting as a blind and homeless Native American is questionable, though he’s as mesmerizing here as he was in “John Grisham’s The Rainmaker,” “Anaconda,” “Ali” and other late career highlights from this period.

#UTurn was the middle film of an unplanned crime trilogy between #NaturalBornKillers (1994) and #Savages (2012). Unappreciated in ’97, it was pulled from most theaters quickly. TriStar disliked it, and reviews were not kind — ‘brutal,’ ‘derivative,’ etc. pic.twitter.com/d4W5MuUc0M

— Oliver Stone (@TheOliverStone) February 3, 2021

Stone once again uses a Native American character to reflect on America’s past, as he did in “The Doors” (1991) though, with both films, it’s an element that serves as subtext and doesn’t overwhelm or become a central theme.

Liv Tyler makes a quick, silent cameo; she was an in-demand actress at this point and her blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance is baffling, though hardly the most bizarre thing here.

Robert Richardson is the film Director of Photography and frequently performs miracles here. Note how his over-exposing some of the scenes makes the imagery simmer. It looks hot, smoky and devoid of life in this world, and we feel trapped just as much as the characters do.

As it was with “JFK” and “Nixon,” the editing is incredible; Bobby’s brief mention of being a former tennis instructor even allows for quick clips of him on the court during happier days. The editing is credited to Hank Corwin and Thomas J. Nordberg, who clearly had oodles of footage to sort out and assemble into Stone’s cracked vision.

Ennio Morricone’s score is sometimes cartoonish, sometimes sinister – the music fits the sun warped mind of our weary protagonist.

At times, “U-Turn” is very funny, such as the moment a scorpion appears and scares Bobby out of drinking from a hose. Stone’s sun-bleached noir gets incredibly ugly by the third act. Stone punishes his audience, and the film gets long winded when it ought to be wrapping up.

After suggesting many heinous things, Stone shows us them, which is unnecessary.

The film is already pretty savage; getting crazy with the carnage and depravity so late in the game doesn’t give this any additional charge, only reminding us that the “Natural Born Killers” director loves excess.

The depravity involving Nolte and Lopez’s characters weighs the conclusion down. Instead of that, why didn’t we get one more welcome, loopy Danes/Phoenix appearance?

Yet, when the story regains its focus in the final scenes, particularly with another hysterical encounter with Thornton, it at least ends strong.

“U-Turn” (actually, it’s really more of a detour) ends on a killer punchline, as a shadow sweeps over characters, blanketing them with death, and the film ends. Stone’s film is savage, overbearing and very funny, a tour de force of acting and filmmaking.

The setting here never feels like a film production façade, as “U-Turn” creates an environment where one could be absorbed by nature, swallowed whole, which is only avoidable if you don’t stop moving. Superior comes across as a town consisting of misplaced members of society.

It’s a real place, too, as Superior is an actual town surrounded by a desert. I’m curious what the Superior town historian thinks of this movie.

Penn is stuck in this town and both the landscape and the town folk begin to feast on him. Death is bearing down on Bobby and everyone in Superior. Do the people of Superior watch this and laugh…or cry?

The post Oliver Stone’s ‘U-Turn’ Is His ‘After Hours’ appeared first on Hollywood in Toto.

0 Comments